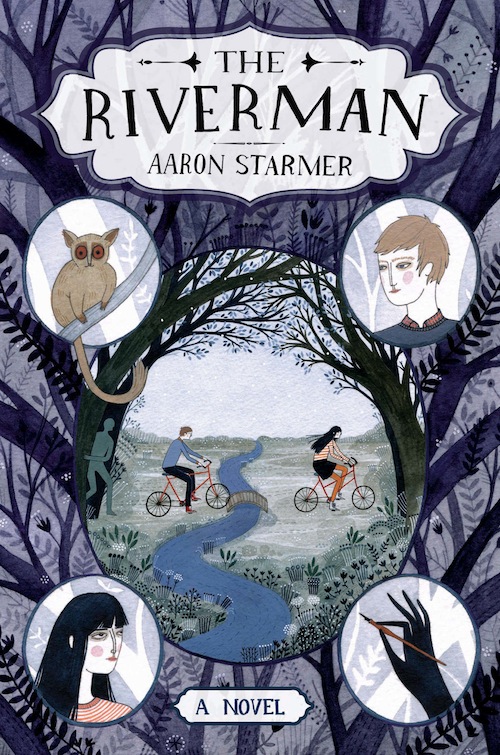

Check out The Riverman, the first novel in a new trilogy by Aaron Starmer, available March 18th from Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Alistair Cleary is the kid who everyone trusts. Fiona Loomis is not the typical girl next door. Alistair hasn’t really thought of her since they were little kids until she shows up at his doorstep with a proposition: she wants him to write her biography.

What begins as an odd vanity project gradually turns into a frightening glimpse into the mind of a potentially troubled girl. Fiona says that in her basement, there’s a portal that leads to a magical world where a creature called the Riverman is stealing the souls of children. And Fiona’s soul could be next. If Fiona really believes what she’s saying, Alistair fears she may be crazy. But if it’s true, her life could be at risk. In this novel from Aaron Starmer, it’s up to Alistair to separate fact from fiction, fantasy from reality.

BEFORE

Every town has a lost child. Search the archives, ask the clergy. You’ll find stories of runaways slipping out of windows in the dark, never to be seen again. You’ll be told of custody battles gone ugly and parents taking extreme measures. Occasionally you’ll read about kids snatched from parking lots or on their walks home from school. Here today, gone tomorrow. The pain is passed out and shared until the only ones who remember are the only ones who ever really gave a damn.

Our town lost Luke Drake. By all accounts he was a normal twelve-year-old kid who rode his bike and got into just enough trouble. On a balmy autumn afternoon in 1979, he and his brother, Milo, were patrolling the banks of the Oriskanny with their BB rifles when a grouse fumbled out from some bushes. Milo shot the bird in the neck, and it tried to fly but crashed into a riot of brambles near the water.

“I shot, you fetch,” Milo told Luke, and those words will probably always kindle insomnia for Milo. Because in the act of fetching, Luke slipped on a rock covered with wet leaves and fell into the river.

It had been a rainy autumn, and the river was swollen and unpredictable. Even in drier times, it was a rough patch of water that only fools dared navigate. Branch in hand, Milo chased the current along the banks as far as he could, but soon his brother’s head bobbed out of view, and no amount of shouting “Swim!” or “Fight!” could bring him back.

Experts combed the river for at least fifteen miles downstream. No luck. Luke Drake was declared missing on November 20, and after a few weeks of extensive but fruitless searches, almost everyone assumed he was dead, his body trapped and hidden beneath a log or taken by coyotes. Perhaps his family still holds out hope that he will show up at their doorstep one day, a healthy man with broad shoulders and an astounding tale of amnesia.

I saw Luke’s body on November 22, 1979. Thanksgiving morning. I was almost three years old, and we were visiting my uncle’s cabin near a calm but deep bend in the Oriskanny, about seventeen miles downstream from where Luke fell. I don’t remember why or how, but I snuck out of the house alone before dawn and ended up sitting on a rock near the water. All I remember is looking down and seeing a boy at the bottom of the river. He was on his back, most of his body covered in red and brown leaves. His eyes were open, looking up at me. One of his arms stuck out from the murk. As the current moved, it guided his hand back and forth, back and forth. It was like he was waving at me. It almost seemed as though he was happy to see me.

My next memory is of rain and my dad picking me up and putting me over his shoulder and carrying me back through the woods as I whispered to him, “The boy is saying hello, the boy is saying hello.”

It takes a while to process memories like that, to know if they’re even true. I never told anyone about what I saw because for so long it meant something different. For so long it was just a boy saying hello, like an acquaintance smiling at you in the grocery store. You don’t tell people about that.

I was eleven when I finally put the pieces in their right places. I read about Luke’s disappearance at the library while researching our town’s bicentennial for a school paper. With a sheet of film loaded into one of the microfiche readers, I was scanning through old newspapers, all splotchy and purple on the display screen. I stopped dead on the yearbook picture of Luke that had been featured on Missing posters. It all came rushing back, like a long-forgotten yet instantly recognizable scent.

My uncle had sold the cabin by then, but it was within biking distance of my house, and I went out there the following Saturday and flipped over stones and poked sticks in the water. I found nothing. I considered telling someone, but my guilt prevented it. Besides, nine years had passed. A lot of river had tumbled through those years.

The memory of Luke may very well be my first memory. Still, it’s not like those soft and malleable recollections we all have from our early years. It’s solid. I believe in it, as much as I believe in my memory of a few minutes ago. Luke was our town’s lost child. I found him, if only for a brief moment.

Friday, October 13

This, my story, starts here, where I grew up, the wind-plagued village of Thessaly in northern New York. If you’re the first to stumble upon my tale, then I can assume you’re also one of the few people who’ve been to my hometown. But if my words were passed along to you, then you’ve probably never even heard of the place. It’s not tiny, but it’s not somewhere travelers pass through. There are other routes to Canada and Boston, to New York City and Buffalo. We have a diner downtown called the Skylark where they claim to have invented salt potatoes. They may be right, but no one goes out of their way for salt potatoes.

Still, this is a pleasant enough corner of the world in which to live, at least when the wind isn’t raging. There are parks in every neighborhood and a pine tree in the center of town where they string blue lights every Veterans Day. There’s a bulb for every resident of Thessaly who died in a war, dating back as far as the Revolution. There are 117 bulbs in all. Unnoticed, we played our part, and there’s plenty of pride in that.

My neighborhood, a converted plot of swamp and woodland that was supposed to attract urban refugees, is the town’s newest, built in the 1950s, a time when, as my mom constantly reminded me, “families were families.” Enough people bought in to justify its existence, but it hasn’t grown. At the age of eight, I realized that all the houses in the neighborhood were built from the same four architectural plans. They were angled differently and dressed in different skins, but their skeletons were anything but unique.

The Loomis house had the same skeleton as my house, and I guess you could say that Fiona Loomis—the girl who lived inside that house, the girl who would change everything—had the same skeleton as me. It just took me a long time to realize it.

To be clear, Fiona Loomis was not the girl next door. It isn’t because she lived seven houses away; it’s because she wasn’t sweet and innocent and I didn’t pine for her. She had raven-black hair and a crooked nose and a voice that creaked. We’d known each other when we were younger, but by the time we’d reached seventh grade, we were basically strangers. Our class schedules sometimes overlapped, but that didn’t mean much. Fiona only spoke when called upon and always sighed her way through answers as if school were the ultimate inconvenience. She was unknowable in the way that all girls are unknowable, but also in her own way.

I’d see her around the neighborhood sometimes because she rode her bike for hours on end, circling the streets with the ragged ribbons on her handgrips shuddering and her eyes fixed on the overhanging trees, even when their leaves were gone and they were shivering themselves to sleep. On the handlebars of her bike she duct-taped a small tape recorder that played heavy metal as she rode. It wasn’t so loud as to be an annoyance, but it was loud enough that you’d snatch growling whispers of it in the air as she passed. I didn’t care to know why she did this. If she was out of my sight, she was out of my thoughts.

Until one afternoon—Friday the 13th, of all days—she rang my doorbell.

Fiona Loomis, wearing a neon-green jacket. Fiona Loomis, her arms cradling a box wrapped in the Sunday comics. Fiona Loomis, standing on my front porch, said, “Alistair Cleary. Happy thirteenth birthday.” She handed me the box.

I looked over her shoulder to see if anyone was behind her. “It’s October. My birthday isn’t for a few months. I’m still twelve and—”

“I know that. But you’ll have a birthday eventually. Consider this an early present.” And with a nod she left, scurried across the lawn, and hopped back on her bike.

I waited until she was halfway down the street to shut the door. Box on my hip, I skulked to my room. I wouldn’t say I was scared when I tore the paper away, but I was woozy with the awareness that I might not understand anything about anything. Because an old wool jacket filled the box, and that recorder from her handlebars, still sticky and stringy from the duct tape, sat on top of the jacket. A cassette in the deck wore a label that read Play Me.

“Greetings and salutations, Alistair.” Fiona’s voice creaked even more when played through the flimsy speaker, but it was a friendly creak. “I hope this recording finds you and finds you well. You’ve gotta be wondering what it’s all about, so I’ll get right to it. You have been chosen, Alistair, out of many fine and distinguished candidates, to pen my biography.

“I use the word pen instead of write because when you write something you might just be copying, but when you pen something it means . . . well, it means you do it like an artist. You dig up the story beneath the story. Last year, you wrote something in Mrs. Delson’s class called ‘Sixth Grade for the Outer-Spacers.’ It takes a unique mind to come up with a tale like that. I hope you can bring that mind to the story of my life.”

“Sixth Grade for the Outer-Spacers.” It was a stupid thing I had whipped off in an afternoon. It was about a bunch of aliens who were old, but looked like human kids. For fun, they would visit Earth and enroll in middle school and do outrageous and exceptional things. It was my explanation for bullies and sports stars and geniuses and rebels and kids you envied because they were fearless.

Mrs. Delson had called it “promising,” which I took to mean it was promising. But you eventually realize something if you’re inundated with empty compliments like that—You’ve got loads of potential, Alistair! You’ve got the makings of someone great, Alistair! It’s all part of a comforting but dishonest language that’s used to encourage, but not to praise. I know now that promising actually means just okay. But just okay was good enough for Fiona, and with every word she spoke on that tape I became more entranced by the idea that I had talent.

“Choice is yours, obviously,” Fiona said. “Maybe you want me to sell it to you. To sell a book, you need a description on the back. So here’s mine: My name is Fiona Loomis. I was born on August 11, 1977. I am recording this message on the morning of October 13, 1989. Today I am thirteen years old. Not a day older. Not a day younger.”

A faint hiss came next, followed by a rampage of guitars clawing their way out from the grave of whatever song she had taped over.

Saturday, October 14

Ten missing months. I was no math wizard, but I knew that a girl born on August 11, 1977, didn’t turn thirteen until August 11, 1990. October 13, 1989, was ten months before that date. Fiona had my attention.

I’m not sure how many times I listened to the tape. A dozen? Maybe more. I was listening to it in bed the next morning when the phone rang. My sister, Keri, knocked on my door, and I stuffed the tape recorder under my pillow.

“It’s open.”

Keri ducked in and tossed the cordless phone my way, flicking her wrist to give it a spin. When I caught it, she looked disappointed, but she recovered quickly, closing her eyes and shaking her hands in the air like some gospel singer.

“It’s Charrrrrlie Dwyer!”

I glared at her, and she shot me with finger guns and slipped away.

“Hey, Charlie,” I said into the phone, feigning excitement.

Charlie was Charlie, blurting out the worst possible question. “If someone asked you who your best friend is, would you say that I’m your best friend?”

I paused for far too long, then replied, “Yeah, Charlie. Most definitely.”

“Got it,” he said, and hung up.

The first thing you need to know about Charlie is that in his backyard there was a clubhouse, built by his older brother, Kyle, five or six years before. In that former life, it was a fortress for neighborhood kids to collect and scheme and just be kids. When Kyle outgrew it, Charlie let it fall into disrepair. Feral cats took over, but rather than scare them away, Charlie left cans of tuna for them and gave them names. It stunk of feces and urine, and no one wanted to go in it anymore. The teenagers in the neighborhood would watch in disgust as the cats squeezed through the rotten holes in the clubhouse’s shingles. They’d say things like, “It used to be so amazing.”

As for Charlie, he was mostly an indoor cat, declawed so he could paw remotes and Nintendo controllers. We had been neighbors and friends since toddling, but it was a friendship of convenience more than anything. So when he asked me if he was my best friend, I should have been honest and said No, I don’t have one. With those simple words, things could have turned out differently. Or not. Speculating is pointless.

The Riverman © Aaron Starmer, 2014